-

8

-

2026-02-11 13:54:10

I had to hear it for myself. We rolled the Focus into bay three, the concrete floor cool under the wheels. I slid into the driver's seat, the familiar smell of old upholstery and fast-food wrappers filling the air. The turn of the key was perfectly normal—that satisfying momentary whir, the engine catching with a healthy shudder. But then, the sound didn't resolve. It didn't settle into the low, lumpy idle of that old four-cylinder. Instead, right as the engine took over, a new, invasive noise grafted itself onto the engine's rhythm like a rusty bandsaw blade hitting wood. It wasn't a deep knock from the bottom end or a light valve tick from the top. This was a harsh, grinding whine that felt like it had physical teeth. It wasn't random; it climbed precisely with the tachometer, a parasitic screech married to every combustion cycle. You didn't just hear it; the vibration traveled up the frame and you felt it in your molars. From his worn stool by the grimy parts washer, Old Zhang—who'd diagnosed more starters by ear than I'd ever pulled—didn't even glance up from the steam rising off his enamel mug. His voice, a dry rasp honed by forty years of Marlboros and shop air, cut through the mechanical wail without raising a decibel: "Bendix is hung up. Kill it now, kid, unless you're buying him a new ring gear for Christmas."

He'd named the beast. "Hung up." It's the shop-floor term for when the starter's drive gear—many of us still use the old brand name 'Bendix' for the mechanism—does its job and then flat-out refuses to retreat. It's stuck in the mesh, and the now-running engine is taking it on a violent, destructive joyride it was never designed to survive.

Why It Gets Stuck: A Cascade of Small Failures

This kind of failure rarely just "happens." It's usually the explosive final scene in a long, slow play of wear and neglect inside the starter's drive end.

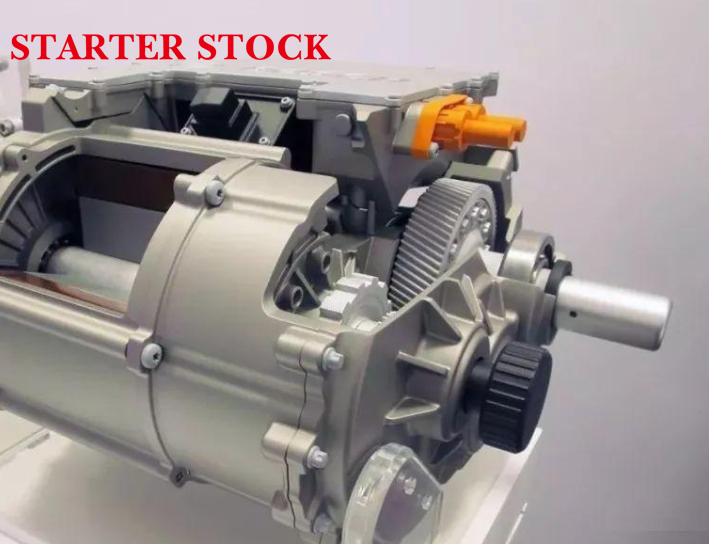

The Spring Loses Its Will. Crack open a starter on the bench. Inside, behind the drive gear, sits a hefty coil spring. Pull a new one out of the box, and it's stiff, stubborn—it wants to stay short and has the strength to get there. Its sole reason for existence is to be the muscle that yanks the pinion gear back the instant the solenoid releases it. But this spring lives maybe two inches from the searing exhaust manifold or engine block. After a decade or two of daily thermal torture—expanding with heat, contracting as it cools—the metal "fatigues." It loses its temper, its resilience. It goes soft. I've compared old and new springs side-by-side; the old one feels limp, defeated, like a tired old dog that won't get off the porch. It might still work on a perfectly clean shaft, but it becomes a weakling against any extra friction. When you're bench-testing a suspect starter and the gear comes out but only slooooowly, reluctantly slinks back in, that spring is whispering its confession.

The Splines Get Gummy, and Everything Seizes. Here's what most people don't see: the pinion gear doesn't just slide straight in and out like a bolt. It travels on spiral splines—think of a steep, threaded ramp machined right into the shaft. It's a clever bit of engineering; the starter's own spinning helps wrench the gear fully into mesh for a solid bite. But these tiny, precise grooves demand cleanliness they never get. They're slathered in factory grease that, over a hundred thousand miles of heat cycles, turns into a sticky magnet. It collects the inevitable microscopic metal dust from the clutch wearing in, mixes with carbon soot from the engine bay, and bakes on road grime. What you end up with isn't grease anymore. It's a hard, black, lacquer-like glue that binds the gear to the shaft. I've torn down starters where the drive assembly was so seized it felt like a single, solid chunk of iron. The fix isn't pretty. You clamp the starter in a big bench vise, soak the end in penetrating oil until the shop clock ticks away an hour, then gingerly tap around the clutch body with a brass punch—ping… ping… ping—hoping the aluminum housing doesn't crack before the bond finally lets go with a sickening crack. A tired return spring hasn't got a snowball's chance in hell against that kind of adhesive.

The Solenoid Forgets to Let Go. We think of the solenoid as an electrical component, and it is—it's the heavy-duty switch that sends the full fury of the battery to the motor. But it's also a mechanical actuator. Inside its chrome-plated can, a heavy iron plunger is linked to a pivoting shift fork, the little metal finger that actually pushes the drive gear. If that fork gets a slight bend from a past, overly-enthusiastic engagement, or if the plunger's cylindrical bore gets packed with varnished grease and carbon grit, the mechanics fail. The plunger sticks in the "engaged" position. Even with the key off and the electrical circuit dead, it remains physically extended, acting like a metal rod holding the gear out against the flywheel. No amount of spring force can retract a gear that's being mechanically blocked from behind.

The Flywheel Bites Back (The Wallet-Killer). This is the scenario that starts with a different problem entirely. If a tooth on the flywheel's ring gear gets damaged—maybe from a previous starter with weak engagement, maybe from simple metal fatigue—it can deform. The tip can bend over or "mushroom," creating a tiny, malicious hook. The starter pinion, with the immense force of the solenoid behind it, can smash past this hook on its way into mesh. But when the engine fires and roars to life, and the pinion tries to spin back along its spiral splines to disengage, that hooked tooth snags it. It's a one-way trap. This changes everything on the repair order. Now you're not just explaining a starter replacement. You're looking the customer in the eye and telling them the flywheel (or flexplate on an automatic) needs replacement—a job that requires separating the transmission from the engine. The labor hours multiply, and the estimate easily triples. It's the worst-case domino effect.

Your Move: The Emergency Drill

Hearing that grinding-whine after startup is a five-alarm fire for your drivetrain. What you do in the next three seconds is the most important diagnostic and cost-saving action you can take.

Ignition Off. NOW. This is not the time for curiosity. Do not pause to "listen and locate." Do not rev the engine to "see if it clears." Your brain should process the sound as "ABORT" and your hand should already be twisting the key to OFF. Every second the engine spins with that gear engaged is actively milling away the hardened surface of the flywheel teeth, turning a potentially salvageable component into guaranteed scrap metal. The sound is the timer; your hand is the stop button.

Do Not Restart. Not Once. I've stood there and watched customers do it, the panic clear on their faces. They shut it off, the sudden silence ringing in their ears. Then the doubt creeps in. "Maybe it was a fluke… just a weird noise." So they turn the key again. Let me be brutally clear: it was not a fluke. That initial, horrific grinding generated intense, localized heat at the points where the steel teeth were grinding. That heat can actually cause a microscopic weld—a "cold weld" where the metals fuse just enough. When you command the starter to re-engage, you're applying several hundred foot-pounds of torque through that potentially fused junction. The result isn't a second chance; it's often the snap of a flywheel tooth shearing clean off, or the pinion gear cracking. You just transformed a "replace the starter and maybe the flywheel" job into a "guaranteed full flywheel replacement, plus possibly fishing metal shrapnel out of the bellhousing" catastrophe. It's the single most expensive mistake you can make in this situation.

The Fix: No Half-Measures, No False Economy

After an event like this, the old starter isn't a candidate for a rebuild kit; it's a "core" for exchange, its useful life obliterated. The shop's logic is uncompromising for good reason:

The motor is internally wounded. Being back-driven at 1,500+ RPM forces it to act as a generator, creating voltage spikes that can fry the delicate insulation on the armature windings and arc the commutator bars to death.

The drive assembly is destroyed. The one-way clutch internals (rollers, sprags, springs) have been subjected to forces they were never designed to handle. They are shattered, ground, or permanently deformed.

Flywheel inspection is an absolute mandate. This is the step that separates a quick parts swap from an honest repair. Before a single bolt of the new starter is threaded in, a mechanic worth his salt will do the tedious work. He'll get a long breaker bar on the crankshaft pulley bolt and slowly, methodically, rotate the engine over by hand. With a bright LED flashlight in one hand and a small, swiveling inspection mirror in the other, he'll peer into the starter mount hole and examine every. single. tooth. on that ring gear, all 130 or so of them. He's looking for the evidence: tell-tale shiny, polished spots where the grinding happened, small chips missing from the leading edge, or the dreaded "hook" where a tooth is deformed and will snag the new gear. Finding any damage means the flywheel gets replaced, full stop. Putting a new $200 starter against a $1,000 flywheel with a hidden wound isn't just shortsighted; in my shop, we call that "kicking the can down the road and handing the customer the bill for the next tow." It's a guaranteed comeback, and it destroys trust.

This is why the industry standard is to install a complete, quality remanufactured starter assembly. The math and the logic are inescapable. You're not buying a questionable rebuild kit from a parts store bubble pack, hoping you have all the right presses and shims. You're certainly not gambling on a "tested used" unit from a junkyard, which is just someone else's problem with the wear baked in. A proper reman unit from a reputable brand is a different beast. They take a core, strip it to a bare housing, and replace every wear item: new solenoid with fresh copper contacts, a completely new drive gear assembly with a tight one-way clutch, new bronze bushings, new brushes, and they often true up the armature commutator. Then they run it on a test stand under real load. You're not paying for a single repaired link in a worn-out chain. You're paying for a system-level renewal. It's the only way to get a predictable, warrantied result and sleep at night knowing you didn't just defer the problem for another thousand miles.

The Final Word

A starter that won't disengage isn't hinting at a problem; it's screaming one through a megaphone made of grinding metal. That awful, rising whine is the sound of a financial countdown timer. Old Zhang, in his later years, would just set down his tools, wipe his hands slowly on a rag that never got clean, and deliver the verdict like a judge passing sentence: "A car that won't start is just being stubborn. A starter that won't quit after it starts has gone rogue. It's not broken—it's mutinying. And your bank account is the first hostage."

Respect the mutiny. Answer its scream with immediate shutdown, followed by a complete starter replacement and a forensic inspection of the flywheel. It's the only path to ensuring your next start is followed by the sweet, affordable sound of silence.